737 MAX MADNESS

BY CAPT. VIC (NOV. 2019)

The two crashes of BOEING 737 MAX aircraft which took place in 2018 and early 2019 sent a cold chill down my spine. The fact that Boeing nor the FAA took any action after the second crash shocked me and I was compelled to issue a warning to my readers not to fly this particular aircraft type. It was no surprise to me when weeks later country after the country started to ground the aircraft. Fortunately, no one else was killed or injured in a MAX aircraft. I’ve followed the story with interest from the beginning and decided to carry out an investigation of my own. It already appeared to me that some kind of an inherent flaw may be lurking in this redesign of the 53-year-old original.

THE BRIEF

To understand what happened its necessary to go back to April 9th, 1967 when the first Boeing 737 flew. The design of this aircraft remained little changed from the one you see in the picture above for decades. Anyone who has flown has probably been on one of these babies at one time or another. Over the years this venerable aircraft accumulated an enviable safety record. Boeing, back in that day, had a reputation of being run by engineers who were innovative and had safety as well as quality at the forefront of everything they did. Years of success rolled by and eventually in 1997 Boeing acquired a big rival called the McDonnell Douglas Corporation. Apparently, this marked a period where the bean counters gained supremacy and risk aversion, as well as cost-cutting, took prominence within the merged entity. Cost-cutting is at the very heart of the problems with the 737 MAX. Originally, the decision had been made to build an all-new aircraft to replace the ageing 737. This would take ten years or more to achieve and involve a high degree of cost. When it looked like a lot of their customers, including the stalwart American Airlines, were about to buy Airbus (which was ready to produce the A320neo) Boeing scrapped plans for building a new aircraft and decided to upgrade the forerunner with band-aid fixes once again. This fix would be very different in scope and execution however than prior revisions.

THE GREMLIN

A 30 year Boeing veteran who led the team of engineers building the MAX was quoted as saying, “The culture was very cost centred, incredibly pressured. Engineers were given targets to get a certain amount of cost out of the aeroplane. There was a lot of interest and pressure on the certification and analysis engineers, in particular, to look at any changes to the Max as minor changes.” The latest variant of this old design had a few modest changes. It also had some very big modifications which combined with some other variables caused two deadly crashes killing nearly 350 innocent human beings who put their trust into the airline and Boeing for safe transportation. In order to compete with their rivals, Boeing needed to find a more fuel-efficient engine with greater range capabilities. They chose the Leap-1B engine designed by CFM INTERNATIONAL which is bigger and heavier than engines on older iterations of the 737.

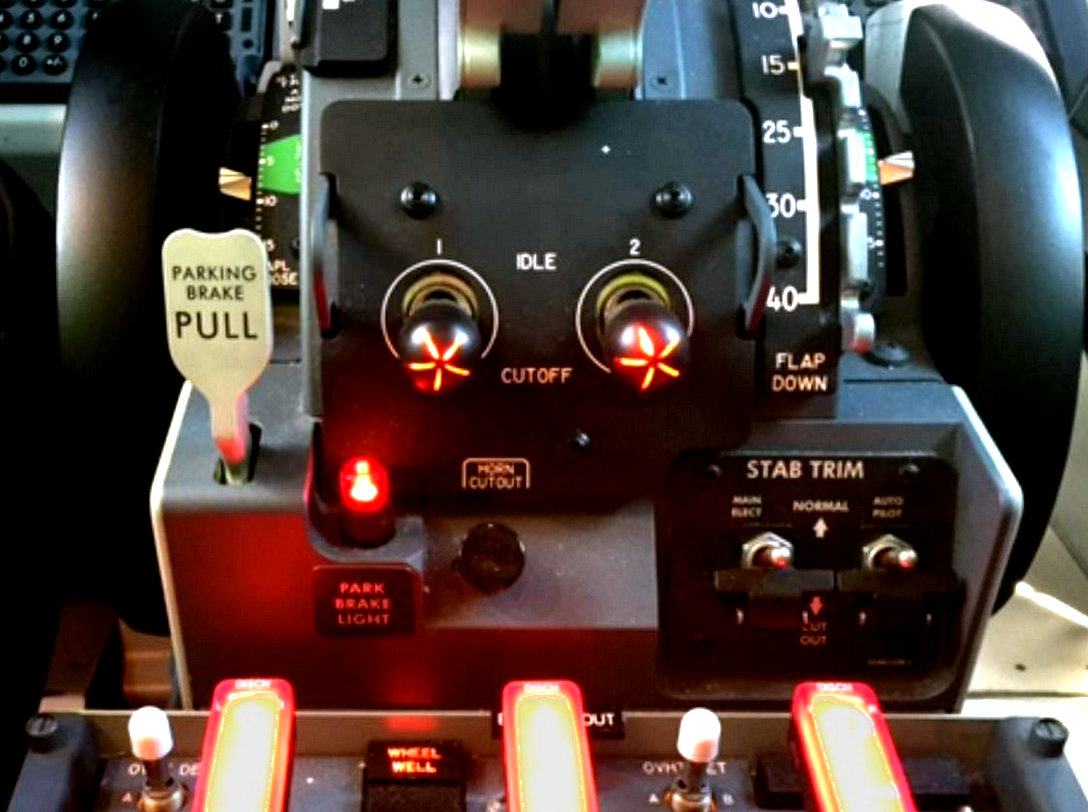

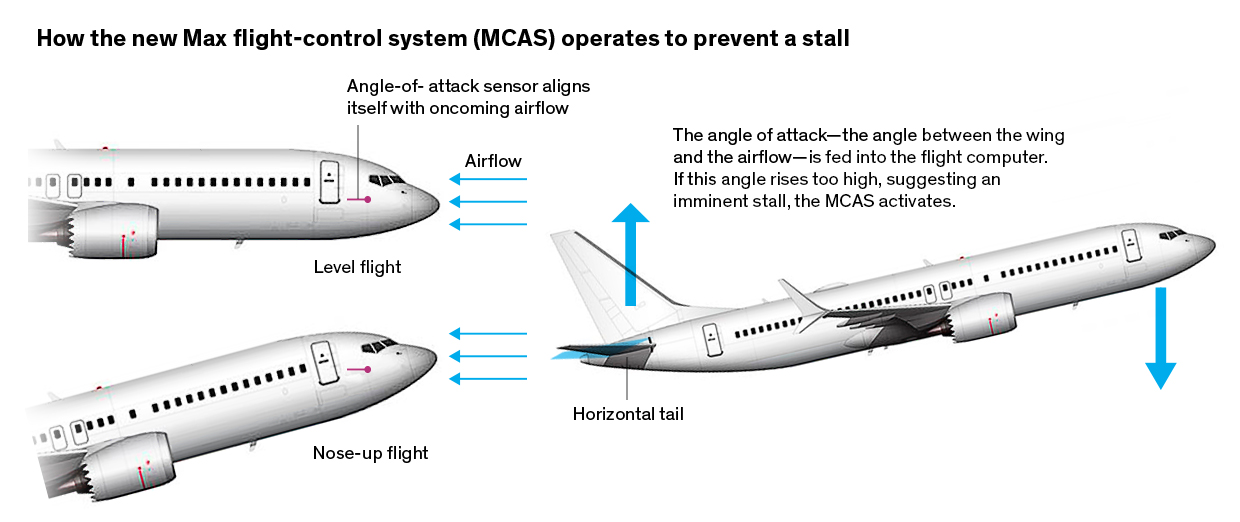

There is nothing wrong with this engine itself. The problem stems from the old 737 not being able to accommodate their large size because of it’s low ground clearance and this resulted in them being mounted forward and higher on the plane’s wing. The aerodynamics of the 737 was fundamentally changed to an unstable configuration! This was no longer your father’s 737 and never should have been certified as such. Boeing should have stopped at this point and looked at ways to change the structure of the aircraft in order to accommodate the larger power-plant or go back to the drawing board and start fresh as was originally planned. They chose instead to continue with the plan of getting the aircraft certified as the old 737 and as quickly as possible! Note the picture above showing how far forward and higher the engine is mounted on the wing compared to older versions of the aircraft. This changed the center-line of the engine’s thrust. Now, when the pilots applied power to the engine, the aircraft would have a significant propensity to “pitch up,” or raise its nose. The engine nacelles were so far in front of the wing and so large, a power increase will cause them to actually produce lift, particularly at high angles of attack ahead of the center of lift, aggravating the situation further and making the aircraft inherently unstable. The chief technical pilot for the Max had complained to a colleague, eight months after he had asked the F.A.A. about removing mention of the new automated system from the pilot’s manual, that the Max had egregious handling characteristics with MCAS at high angles of attack. Both of these accidents took place at high power settings and high angles of attack close to the ground. To counter these stability problems Boeing created the MCAS (Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System) software and kept it quiet in order to maintain the current type certification and avert extra training and maintenance costs. They wanted everyone to think that this was just another 737. To say that Boeing was about to let professional pilot’s and the flying public down would be a gross understatement. At the congressional hearings, where the Boeing CEO appeared this week, one congressman put it to him this way “Those pilots never had a chance,” Blumenthal said. “Passengers never had a chance. They were in flying coffins as a result of Boeing deciding that it was going to conceal MCAS from the pilots.”

THE DEVIL IN THE DETAILS

What happened? Due to cutbacks and low staffing levels at the FAA increasing amounts of work relating to certifying the safety of an aircraft were delegated to Boeing over the years. As mentioned earlier, there were increasing pressures to conform to timelines in order to get the MAX out as soon as possible. More and more of the certification process was done by Boeing designates and some of it, including the MCAS system, was never fully reviewed by the Federal Aviation Administration (F.A.A.) which lacked the capability to effectively analyze much of what Boeing did share about the new plane. The FAA has admitted to being incompetent when regulating software, and, as a policy, it allows plane manufacturers to police themselves for safety. Nowhere in its amended type certification of the 737 Max is MCAS even mentioned. The aircraft, because of the engine change, already should have failed the ability to be re-certified as the old model and now, because of that change, a new component had to be added as a band-aid fix for the additional problems associated with that change. This fix, the MCAS software, also should not have been certified as it was. MCAS received a “hazardous failure” designation. This meant that, in the FAA’s judgment, any kind of MCAS malfunction would result in, at worst, “a large reduction in safety margins” or “serious or fatal injury to a relatively small number of the occupants.” Such systems, therefore, need at least two levels of redundancy, with a chance of failure less than 1 in 10 million. The MCAS had no redundancy. It relied on one AOA (ANGLE OF ATTACK) sensor for input information and the rest was up to the computer to decide without any regard for what human beings thought about the situation. These same AOA sensors were highly unreliable. In its report, commissioned by the FAA, the Joint Authorities Technical Review panel found that Boeing withheld critical details about MCAS from the FAA, saying MCAS “was not evaluated as a complete and integrated function in the certification documents that (Boeing) submitted to the FAA.”

MCAS

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was designed as an augmentation to the already existing Elevator Feel System (EFS) which along with some other systems and sensors provides additional push pressure on the yoke during the approach to a stall. There are a couple of items about this system that indirectly led to the crashes. The system relied on one sensor to determine that a stall configuration was immanent. It operated far quicker and with much greater force than was originally stated by Boeing in the certification documents and it operated without pilot participation or awareness. The system had the capability to reset after 5 seconds of normal flight thereby setting up a negative feedback loop between the pilot and the computer (computer pushing the control forward and pilot trying to pull the control column back) witch had lethal consequences. A spokesman for the American Airlines Pilot’s, Dennis Tajer, put if this way,

The following is an abbreviated summary of the text from the flight voice recorder on Lion Air flight 043 which arrived in Jakarta to become the doomed Lion Air 610 flight the next morning:

The first sign of trouble appeared just after takeoff. Inside the cockpit of the 737 Max belonging to Lion Air, the stick shaker on the captain’s side began to vibrate. Stick shakers are designed to warn pilots of an impending stall, which can cause a dangerous loss of control. As the name implies, it shakes the control column in response to input from various sensors and flight deck computers. But the airplane was flying normally, nowhere near a stall. About 30 seconds later, the Captain noticed an alert on his flight display — IAS DISAGREE — which meant that the flight computer had detected a sensor malfunction. He said, “you have control” to the First Officer and began a troubleshooting process according to company training. He found that his instruments on the left side were getting bad data and then flipped a switch that essentially provides data from the right side computer. Everything appeared normal at that point and the Captain assumed that the problem was solved for the time being.

At 1,500 feet of altitude, the takeoff segment was complete and the First Officer began the initial climb. He adjusted the throttle, set the climb pitch, and retracted the flaps. Except the airplane didn’t climb. It nosed sharply downward toward the ground. The first officer reacted instinctively. He flicked a switch on his control column to counteract the dive. The airplane responded right away, pitching its nose back up. Five seconds later, it dove once again. The first officer brought the airplane’s nose up the third time. It pitched back down.There was no memorized emergency checklist that seemed to apply to this situation. The Captain scooped up the airplane’s Quick Reference Handbook (QRH). The QRH is a series of checklists that are designed to help pilots rapidly assess and manage “non-normal” situations. After quickly running through the QRH it appeared as if nothing in the manual applied to the situation. Over the next six minutes, as the First Officer struggled to control the airplane and the Captain searched for the right checklist, the aircraft climbed and dove over a dozen times. At one point, the airplane pulled out of a 900-foot dive at an airspeed of almost 375 mph, which is uncomfortably close to the 737’s “redline” of 390 mph. They were close to losing control of the aircraft in what now must have been terrifying moments in the flight-deck. At this moment, an off-duty pilot riding as a jumpseater respectfully offered his assistance to the crew and asked, ” What about the runaway stabilizer checklist?”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16201790/VRG_3380_Runaway_Checklist.jpg)

The crew followed the checklist to the letter and a successful conclusion. The aircraft stopped pitching and appeared to fly normally. An hour later this crew and passengers made a landing at Jakarta airport. The Captain logged and reported the events. Maintenance inspected the aircraft, found nothing wrong, and returned the aircraft to service.

THE DEBRIEF

These crashes should never have occurred. This aircraft should never have been built. At the time of this publication, the investigation into these tragedies is continuing. To date, some startling facts are emerging. In order to cut costs and fast forward a design that was being built to try and compete with a rival, that was far ahead of them with a new aircraft, Boeing had created a toxic culture on the shop floor that led to mistakes from flawed design and decision making processes creating this death trap called a 737 MAX. Instead, the staff was coerced and encouraged to cut corners and even hide crucial changes that were implemented. It gets worse. The F.A.A. delegated more authority to Boeing to have its own people certify manufacturing, engines, and software. Boeing helped craft legislation related to approving designs in a way that suited them and their customers. The F.A.A. never fully reviewed the MCAS system or was aware of errors on some of the performance statistics originally purported. Because this aircraft is inherently flawed in its design and structure, and will never be safe to fly in the current configuration, I’m advising my readers not to use it should it be returned to the skies. I would not trust statements made, by the CEO’s of Boeing, the F.A.A., or the various airline CEOs, that this will be, “the safest aircraft in the sky.” I’ll close with comments from an Airline Pilot’s pilot. A man who represents the epitome of the piloting profession. Many of you will remember him as part of the heroic crew that flew a crippled airliner safely to a water landing. It became known as “The miracle on the Hudson.” The Captain’s name is “Sully” Sullenberger. The highlighting of the text is my own.

Letter to the Editor.

Capt. “Sully” Sullenberger

New York Times Magazine

Published in print on October 13, 2019

In “What Really Brought Down the Boeing 737 MAX?” William Langewiesche draws the conclusion that the pilots are primarily to blame for the fatal crashes of Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian 302. In resurrecting this age-old aviation canard, Langewiesche minimizes the fatal design flaws and certification failures that precipitated those tragedies, and still pose a threat to the flying public. I have long stated, as he does note, that pilots must be capable of absolute mastery of the aircraft and the situation at all times, a concept pilots call airmanship. Inadequate pilot training and insufficient pilot experience are problems worldwide, but they do not excuse the fatally flawed design of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) that was a death trap. As one of the few pilots who have lived to tell about being in the left seat of an airliner when things went horribly wrong, with seconds to react, I know a thing or two about overcoming an unimagined crisis. I am also one of the few who have flown a Boeing 737 MAX Level D full-motion simulator, replicating both accident flights multiple times. I know firsthand the challenges the pilots on the doomed accident flights faced, and how wrong it is to blame them for not being able to compensate for such a pernicious and deadly design. These emergencies did not present as a classic runaway stabilizer problem, but initially as ambiguous unreliable airspeed and altitude situations, masking MCAS. The MCAS design should never have been approved, not by Boeing, and not by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The National Transportation Safety Board has found that Boeing made faulty assumptions both about the capability of the aircraft design to withstand damage or failure, and the level of human performance possible once the failures began to cascade. Where Boeing failed, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) should have stepped in to regulate but it failed to do so. Lessons from this were bought in blood and we must seek all the answers to prevent the next one. We need to fix all the flaws in the current system — corporate governance, regulatory oversight, aircraft maintenance, and yes, pilot training and experience. Only then can we ensure the safety of everyone who flies.

- Capt. “Sully” Sullenberger